Tea History

China is rightly considered the cradle of the world’s tea culture. The original tea tree was found in Yunnan Province over 4,000 years ago.

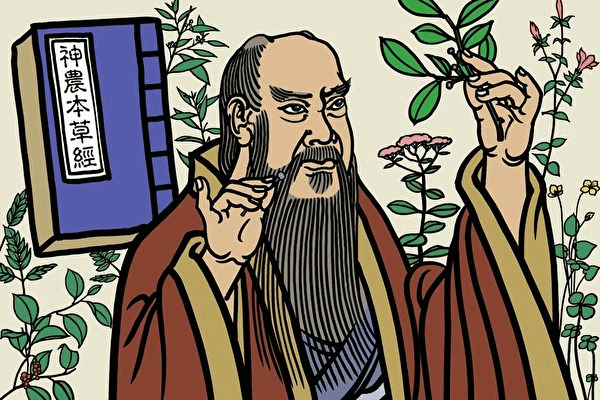

According to a legend, tea was first discovered by the Divine Farmer Shen Nong (2737-2697 BC). Shen Nong had a body made of transparent jade and through his skin, one could clearly see everything happening inside of him. He used this ability to test various herbs to locate medicinal ones among them. In those long-ago days, people of China had been struck with a plague. Shen Nong started looking for a medicinal herb to heal the people from that serious ailment. This is how tea came to be discovered. According to another legend, tea neutralized effects of poison in Shen Nong’s body. “On a single day Shen Nong had tried one hundred kinds of herbs, 72 of those turned out to be poisonous; he took some tea and the tea made the poisoning disappear.” (Shennong's Compendium of Materia Medica, Han dynasty (25-220 AC)). Since then tea takes up a special place in the vegetable kingdom: it is singled out in “a hundred (meaning many herbs, almost all of them) of herbs” and has been called “medicine against a hundred ailments”. Shen Nong’s treatise on food says: “When consumed regularly for a period of time, tea endows the body with strength, the mind – with satisfaction, the will with resoluteness.”

According to another ancient story, tea first appeared thanks to a legendary monk Bodhidharma, the founder of Buddhism who prayed to Buddha to send him a means to help stay awake during meditation.

One day he was fighting sleep getting in the way of his meditating. Having tried everything he knew of, furious, he tore off his own eyelids and threw them onto a slope of Mount Cha. New shoots sprung up on that spot. Those were the new shoots of tea.

At first, tea had been used as a medicinal herb. Fresh raw leaves of a tea tree used to be carefully chewed. Later the leaves were boiled into an infusion which was then consumed as a soup or a stew. Guo Pu (317-420), the father of feng shui in China, wrote: “Tea tree is as small as a gardenia. The leaves which grow even in winter can be boiled and swallowed as a soup.” The leaves were also shaped into flat cakes which were then baked in special ovens and later ground into a powder and poured into porcelain tea canisters.

Later, tea growers started to leave raw tea leaves in the sun to dry and then store the sun-dried leaves. Tea was first purposely cultivated in the gardens and parks adjacent to palaces of Chinese rulers. During the Han Dynasty (207 BC - 220 AC) the tradition of tea cultivation and drinking spread beyond imperial residences and, step by step, started putting its roots among common people. Tea drinking was gradually transforming into a national custom, well-to-do families and wealthy landowners even started to collect specialized tea utensils.

In the days of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AC) the tea industry began to develop rapidly. Tea culture was spreading around the country thanks to the Buddhist and Taoist monks.

Lu Yu wrote the “Tea Canon”, the fullest and the most comprehensive treatise on tea in the first year of the Tang Dynasty. This document has played an important role in the establishment and spreading of tea culture.

According to the legend, Lu Yu was brought up in a Buddhist temple and adopted his mentor’s knowledge of the art of tea preparation. He studied the subtleties of tea theory and took part in discussions dedicated to tea. Lu Yu used this information and, combining it with knowledge of his ancestors and contemporaries, created his “Tea Canon”, in which he shed light on the matters of a tea tree origin, described tools used for tea cultivation and tea drinking utensils, provided descriptions of tea production techniques, the art of preparing tea infusion and the methods of tea drinking, and gave definition to what is called to be tea. At the time Lu Yu was writing his “Tea Canon” there existed up to 10 different names for tea. The most widespread symbol used for tea was 荼 (tu), differing from 茶 (cha), the contemporary symbol for tea, changed by adding just one line.

Publishing of “Tea Canon” led to tea drinking traditions spreading all over China, and tea became a statewide national drink.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279) tea houses and pavilions started to appear selling freshly brewed tea. Tea producing areas were spreading all over, and tea producing technologies were being improved. At the time tea contests became quite popular among the noble and creative elite; these gained significant development over the next few centuries.

During the Song Dynasty tea was started to be actively exported to neighboring countries via the caravan routes.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) the method of pressing tea into flat cakes was gradually abandoned. New technologies of tea processing started to develop. Green, Red, Black, and Scented teas became available. One of the Ming epoch’s most significant achievement is the discovery of vegetative tea tree propagation method.

Finally, the decline of the Ming Dynasty and the dawn of the Qing epoch were marked by the wonderful discovery which turned the tea world upside down – a unique method of tea processing. This is the discovery we are grateful to China for even till this day – a unique method of oolong tea production.

In the past centuries, tea production has changed significantly so we can witness these transformations even today: loose-leaved tea has firmly replaced bing-cha (the tea pressed in the shape of flat cakes); the absolute prevalence of green tea has transformed into varieties of tea species and sorts available.

Great old poets, men of letters, and statesmen praised tea in their works.

Lu Yu called it “a wonderful tree from the south”, a remarkable poet Su Dong Po used to compare it to a beautiful maiden, Emperor Qian Long who lived during the Qing Dynasty compared it with an “a delicate juicy heart of a lotus flower”.

According to some historical sources, tea-drinking traditions have been adopted in many cultures from China. Tea came to Korea and Japan in the 8th-9th centuries AD. Tea spread into the neighboring countries via caravan routes. It first appeared in Russia thanks to Cossacks in the 16th century, but the active tea trade ties between China and Russia only in the 19th century. Since the 17th century, it started to gradually win over the European countries. In 1699 the first British ship after selling its goods in China sailed back to Britain loaded with silk and a peculiar herb which was called tea.

The tea, warmly welcomed in the royal court, became a trendy drink of social events of the day. Trade was vital for England at the time. Tea, silk, and spices were bought in China for selling abroad, while the cotton fabric, yarn, alcohol, opium, and guns (cannons, cannonballs and case shots) were brought to China to be sold.

In a little over 50 years tea gains wide acclaim on the West becoming the most popular drink in Europe; in England – then the world’s largest commercial power – in particular.

20 years later, tea is the government’s main source of income from internal tax revenues, and by the end of the 17th century, the state exchequer is practically emptied by the outflow of silver to China (the tea leaf is paid for in cash) this taking the proportions of a national disaster.

During the entire 18th century the British East-Indian Campaign, a giant half-private and half-state-owned corporation which by a special act of Parliament had been granted undivided rights to trade with India and the rest of Asia, would offer anything in exchange for silver: cotton cloth, weaving tools, cannons, ships. This, however, would yield nothing but haughty refusals of Chinese Emperors who believed China to be capable of fending for itself and felt contempt for the barbarians, as they then used to call all the non-Chinese. Chinese rulers viewed other countries as China’s liegemen.

That was the moment when a British vessel secretly carrying a load of opium arrived in China. Opium had long been known to the Chinese but not easily accessible. Residents of Yunnan Province where opium poppy was grown or the wealthy who could afford it – were the only ones who could get their hands on it. So the British ship was carrying contraband. The East-Indian Campaign, however, did issue a permit to sell opium to the Chinese, albeit for silver exclusively. Opium then becomes the main commodity imported to China. The East-Indian Campaign quickly monopolizes its world supply outside the territories of Yunnan Province and the Ottoman Empire. In 20 years that follow the amount of silver made on opium trade equals out to the debt for tea and silk. The trade balance is restored.

After that, the trade balance shifts in a different direction as opium consumption in China turns out to be 20 times bigger than the consumption of tea by Western Europeans; silver starts pouring into the pockets of Europeans.

Opium entirely transformed the nature of Chinese-Western trade having turned from a means of managing the trade deficit into a powerful psychological weapon. The extent to which the drug had spread was staggering. The abundance of opium was leading to the demoralization of the Chinese population and finally ended in so-called “opium wars” between China and Great Britain, in which the latter came out the winner.

As a result of these events, tea production in China fell, and the Europeans made a decision to grow tea independently, their Indian colonies seemingly suitable for this enterprise in the best possible way.

But, alas, the Europeans failed at fully unraveling the mystery of Chinese tea production.

Tea had been produced in China by authentic technologies that had taken centuries to perfect. Tea production know-how had been passed on from generation to generation not going beyond the boundaries of family clans; simply replicating or imitating these traditions was impossible. Besides, the tea tree turned out to be quite a capricious plant demanding a particular kind of soil and climate. This is why British tea plantations in India, although “had stricken root”, weren’t yielding tea with the same qualities as tea grown in China, the homeland of the tea plant.

This fact explains the common notion existing in the tea world: there is Chinese tea and there is everything else.

Contemporary tea trade in China, being founded on ancient knowledge and permeated with centuries-old wisdom, is carried out to perfection. There have been practically no changes to the age-old traditions of tea cultivation and its manual processing technologies; therefore, even today we have the perfect opportunity to taste the tea which at some point had been, perhaps, the favorite of the Emperor of some distant and powerful dynasty.

Tea for the Chinese is part of the culture of China, an integral part of everyday life. A visitor to China will encounter tea houses, classical or contemporary, anywhere he goes. Tea in China is consumed everywhere, at any time of the day and in every state of mind.

Lin Yutang, a respected writer of the Qing epoch, wrote: “The Chinese know how to truly delight in tea. They drink it at home, in teahouses, when taking counsel together, during feuds or disagreements, and in the deep moonlit night”.

When the Chinese drink tea, they do it not to simply experience its flavor. They strive to enter the tea’s “state of soul”. It is no accident that tea is used as a spiritual component in Chinese religions (Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism), assisting one in immersion into a meditative state, clearing the mind and expanding one’s consciousness. The attitude of the Chinese to tea as a sacred drink is described in poetry and prose. This is how the poet Huang Tingjiang (1045-1105) was praising it in his poems: “Its taste is thick and rich, and fragrance endless. It is like when walking the roads of the kingdom of dreams and beautiful pictures appear in front of you. And, as if lit up, the images of my old friends arise in front of me, and there exists no tens of thousands of li between us anymore. This can’t be put into words, the soul rejoices and I am submerging inside myself.”

Lu Tong, a poet who lived in the days of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) once sent his friend a poem about tea, which got to us under the name of “Seven Cups of Tea”.

The meaning of the poem is as follows:

“The First cup moistens the larynx and the lips;

the Second cup destroys the feeling of stuffiness in your heart.

The Third one - penetrates the most dried-up depths of you, and so you can write five thousand volumes;

the Fourth – releases light perspiration, and all the hardships of worldly life escape through your pores,

the Fifth clears the muscles and the skin,

the Sixth – opens the way to the soul,

the Seventh one though is not to be drunk, for you could feel a light wind picking you under your arms. In what land does Mount Penglai lay, where the Yu Chuang Zi ship skims along driven by this wind.”

At the end of the poet, Lu Tong advises against continuing the tea-drinking since the wonderful taste of the Seventh could take the person so far from worldly cares, that he would become light enough to be carried away onto Penglai— The Island of the Immortals.